Mornings at Villa Bozio, perched at the top of Pieve di Camaiore in Tuscany, begin early. Reveille at Pardes Chana—the girls division of Camp Gan Israel Italy—is at 8 a.m., although campers who want to make it to Cocoa Club better be up earlier than that. Lineup, held in the 16th-century house’s fading pink and orange courtyard, is at 8:20 sharp. That’s followed by morning prayers and then breakfast—fresh bread, butter, jam, mozzarella. From there goes the rest of the camp day, all set to the tune of Chassidic music blaring from loudspeakers.

However early even the youngest campers arise, they likely have nothing on Villa Bozio’s previous inhabitant, sculptor Jacques Lipchitz (1891-1973), who would get up each morning at 6 a.m. “You see, a sculptor is like a chicken,” he told interviewer Milton Krents in 1970. “ ... Because he wakes up with the light, and when the light goes away he is finished ... ”

The great artist, born Chaim Yaakov Lipchitz in the resort town of Druskininkai, today Lithuania, spent the pre-war years in Paris, where he was friends with Picasso (much more so than with Braque), posed for Modigliani (whom he introduced to Soutine), and met Hemingway at one of the parties he regularly attended at Gertrude Stein’s (although back then he didn’t know enough English, nor Hemingway French, to communicate). He escaped from Paris just before the Germans marched in, eventually making his way to New York. Lipchitz made his first visit to Tuscany in 1962, drawn by the millennia-old marble quarries of Carrara—“Michelangelo’s territory” he called it—and the foundry of Luigi Tommasi in Pietrasanta. He and his wife spent six weeks there, with almost all of the artist’s time consumed by work, going from the place he was staying to the foundry and back. “I didn’t see anything [of] Italy,” he said.

But he was smitten, with the work, with the place, and told his wife, Yulla, that they had to return. Unable to find an appropriate rental, “I found a place where I could buy ... a very beautiful house.” The renaissance structure, formally known as Villa Orsucci di Bozio and sometimes spelled Villa Bosio, stands at the pinnacle of Pieve di Camaiore, overlooking the town of Camaiore and offering stunning views of the Tuscan countryside. Lipchitz set up shop there, working on smaller pieces in his indoor studio, and larger ones in the field outside.

Lipchitz was generous with his sprawling new home. “I wish to express to you my deepest gratitude ... for the kind attentions granted for the wedding of my daughter which took place at Villa Bosio, thanks to your very kind offer,” wrote Tommasi, the foundry owner, in 1963. They were “enchanted” celebrating the wedding “in such a dream-like place with such surroundings that made things appear like in a fairy-tail [sic] story.”

Taking inspiration from Lipchitz’s generous spirit as well as his deep commitment to Judaism—inspired by the Rebbe, Rabbi Menachem M. Schneerson, of righteous memory, at the age of 67 Lipchitz began putting on tefillin every day, at some point stopped working on Shabbat, and even described himself to Krents as “a religious Jew”—following his passing a decade later, the Lipchitz family donated Villa Bozio to Chabad-Lubavitch of Italy, and since 1976 it has served as the grand and simultaneously homey setting for Camp Gan Israel Italy and its sister camp, Pardes Chana.

“The kids wake up and go to sleep with beauty all around them,” says Batsheva Helena Goldreich, 18, who spent this summer as a counselor there, and who shot this photo essay for Chabad.org. “It’s breathtaking, and it just creates a lighter, happier, closer atmosphere.”

Replanting Judaism in Post-War Europe

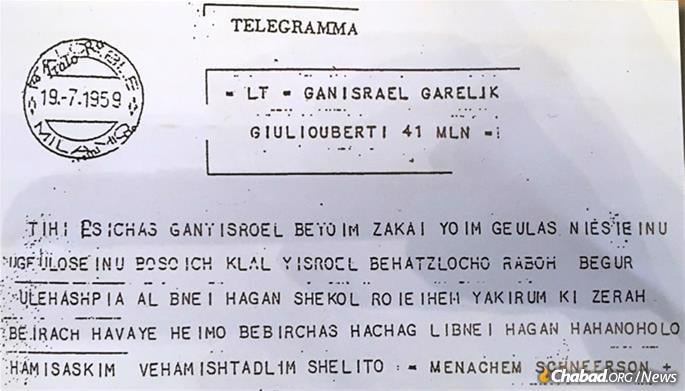

Camp Gan Israel Italy, which will celebrate its 60th anniversary next year, was opened by Rabbi Gershon Mendel and Bassie Garelik in the summer of 1959, the first of its kind in Europe. The Gareliks had arrived in Milan just six months earlier, sent by the Rebbe as his emissaries to Italy. Arriving in Milan on Dec. 1, 1958, the newlyweds established the first Chabad-Lubavitch outpost in the country and hit the ground running.

“Before we left Rabbi [Chaim Mordechai Aizik] Hodakov [the Rebbe’s chief secretary] told me I should start with a kindergarten,” recalls Bassie Garelik, who turned 20 not long after arriving in Italy. “He said ‘they’ll be your greatest collaborators.’” While not completely comprehending at the time, with the benefit of more than a half-century of hindsight she now understands what he meant. “The idea that these children would grow up one day seemed like a lifetime away to me, but today I can introduce you to hundreds of community members throughout Italy who went through my preschool.”

Her father, Rabbi Sholom Posner, had founded Yeshiva Schools of Pittsburgh, and she grew up with a passion for children’s education. So when she landed in Milan with her new husband, the preschool became her very first project. Then, as summer approached, she decided to open a Jewish camp for children (she notes that her husband supported all her initiatives). Summer camp was a new concept for the Italian Jews, almost all of whom were Holocaust survivors building new lives upon the ruins of the old.

“They didn’t like the idea,” she says. “It was 14 years after the war, during summer vacation the parents wanted to take their children to the sea or the mountains, not send them away to a ‘camp.’” It was not only the obvious connotation they disliked; while Chabad’s kindergarten proved popular, when the Gareliks later began planning to open a full Jewish elementary school they got pushback as well. “It was all uphill. A full Jewish school was seen as something from the past, it was just too much.” A Jewish summer camp fell in a similar category, perceived as too intense.

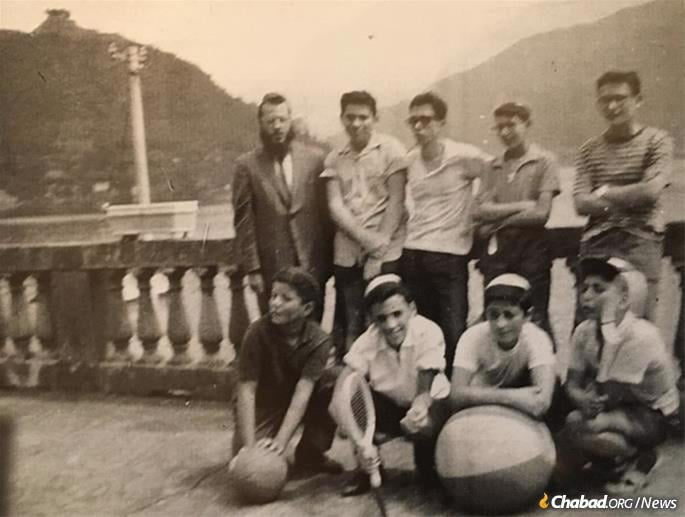

But the Gareliks had special local supporters as well, such as Shlomo Yosef “Carlo” Zippel. He had been the one to initially ask the Rebbe to send a young rabbi to Milan, someone who could appeal to the young people, and once the Gareliks arrived assisted them in any way he could. That summer of 1959 Zippel purchased a home on the Italian side of Lake Lugano. With Bassie Garelik directing, a camper’s mother the cook and two American yeshivah students as counselors, Camp Gan Israel opened its doors with 10 campers.

“Don’t ask me why we opened Gan Israel, no one told us to,” she says. “It just seemed like the obvious thing to do.”

The first day of camp was 13 Tammuz, corresponding to July 19, 1959, and the anniversary of the liberation of the sixth Rebbe—Rabbi Yosef Yitzchak Schneersohn, of righteous memory—from Soviet imprisonment three decades earlier. At a farbrengen gathering held that same day in New York, the Rebbe spoke about the deep impact the authentically Jewish atmosphere of Gan Israel could and was having upon children and their parents. He also shared the good news he had received of the opening of Europe’s first Gan Israel, mentioning the Gareliks by name.

“From this we are able to see how much can be impacted,” the Rebbe said, speaking in Yiddish about the Gareliks’ general mission in Italy. “ ... A lone couple sets out, they establish a school for boys and a school for girls, teach classes to adults ... [She is] a young woman born in America, [he] a young man born in Russia, G‑d Almighty ... introduces them to each other in the United States, and after that they’re sent—farshikt [exiled], so to speak—to Magna Graecia, and there they accomplish all there is to accomplish, and their ‘arms remain outstretched [to accomplish more]’ ... ”

The Rebbe then turned his attention to the camp specifically, stating that the Gareliks had not the money for it, but took out a loan; nor even the children, but had somehow gathered, one by one, enough campers to open their doors.

“Thus in the vicinity of Rome, which ‘through the destruction of Jerusalem, Tyre grew powerful,’ [Rashi’s commentary on Toldot 25:23] and refers to the Roman Empire, a Camp Gan Israel has opened on the 13th of Tammuz in the year 5719, in the Sabbatical year, which will spread the wellsprings, and through the children will impact their parents!”

The Rebbe’s strong words of support for the Gareliks’ nascent efforts was also an exhortation to those in the audience to follow their example and go where they were sent, as well as to see with clear eyes the significance of the work at hand and their inherent power to accomplish it. While Chabad’s network of emissaries has since then grown to more than 4,000 couples, back then it was just a handful of pioneers, the Gareliks in Milan on the frontlines.

Decades later Bassie Garelik remembers sitting on a Jewish educational panel in Milan. In the midst of a conversation about experiential learning, a panelist at the other end piped up. “I didn’t recognize who he was, but I hear him say ‘The first time I experienced Shabbat was in Camp Gan Israel!’”

The next year the summer camp drew more than 30 children, and the next year more than that. The campers were coming not only from Milan, but from throughout Italy, and soon enough there were kids from the United Kingdom, France, Belgium and Switzerland. Parents started getting used to the idea, and in an age when summer vacation in Italy stretched for four months—from May 31 to Oct. 1—they found time to send their children to a Jewish summer camp for a few weeks. When Rabbi Moshe and Henya Yehudis Lazar joined the Gareliks in Milan in the early ‘60s, camp really took off.

“When Moshe Lazar came it really flourished,” says Garelik. “He was ‘Mr. Camp’ in America, so he brought it to another level.”

On a Hilltop in Italy

Gan Israel quickly outgrew the Zippel’s lake house and they began renting campsites in various resort areas throughout Italy. It was 14 years after its founding that Gan Israel finally received its permanent home from the Lipchitz family.

Villa Bozio’s path from the Tuscan studio of one of the 20th century’s greatest sculptors to Chabad overnight camp begins with the deep bond Jacques Lipchitz formed with the Rebbe, which can be explored in depth here. In the late 1950s, the sculptor had been very ill with cancer, and following the suggestion of his brother-in-law, had his wife, Yulla, request a blessing from the Rebbe. The Rebbe assured Yulla that her husband would live, and asked that Lipchitz visit him when he felt able. When he finally did come—coincidentally, also in July of 1959—the Rebbe asked him to put on tefillin each morning, even personally sending him a pair, and suggested that he divorce his first wife according to Jewish law. Lipchitz did both, and a personal relationship developed. Aside from numerous personal audiences, Lipchitz would write to the Rebbe in French, receiving replies in English, resulting in a fascinating and wide-ranging correspondence.

Lipchitz also formed a friendship with one of the Rebbe’s secretaries, Rabbi Yehuda Krinsky, who likewise served as a link between the Rebbe and Lipchitz.

Thus, before going to Italy that summer of 1962, Lipchitz informed the Rebbe of his plans, to which the Rebbe replied in a fairly long postscript to a letter, echoing the words he had spoken at the farbrengen three years earlier:

In view of your mentioning that you plan a trip to Europe and to work in Italy, I trust you may have an opportunity to visit Milan and get acquainted with a young couple, Rabbi and Mrs. Garelik (Via Giulio Uberti 41). Rabbi Garelik was born, and for the first decade of his life brought up, under the Bolshevik regime. His wife is an American-born girl, who gave up all the amenities of American life to join her husband in a mission to spread Yiddishkeit [Judaism] in Italy, especially among the young generation. Despite initial difficulties and the language problem, they have succeeded in their work thanks to their dedication and inspiration which have won them recognition and admiration. It goes to emphasize the common bonds which unite Jewish people everywhere by means of the Torah and Mitzvoth which are eternal and know of no boundaries. In a sense, the art of sculpture is analogous, in that by means of the creative idea it animates the inanimate raw material, giving it form and life that evoke responses in the viewer ...

Lipchitz and his wife did seek out the Gareliks, and from then on Rabbi Garelik would from time to time visit Lipchitz at his Tuscan home, about a three-hour drive south of Milan. There was one time when Garelik got an urgent call from the Rebbe’s secretariat in New York on the eve of Passover to make sure the Lipchitzes had matzah for the seder. With no time to spare, Rabbi Garelik roped in a young member of his community who owned a Porsche, and the two sped there and back in the sports car, making it home in time before the holiday. Another time when Garelik showed up, the butler informed him he would have to wait, for the master was in the middle of his prayers, meaning he was wearing the tefillin the Rebbe had sent him.

When Lipchitz passed away in 1973 on the island of Capri, Garelik received yet another call from Chabad headquarters directing him to go straight there and assist with the sculptor’s Jewish burial, which he did, accompanying the deceased all the way to Jerusalem, where he was buried on Har Hamenuchot.

A short while later the Lipchitz family called Krinsky and told him they wished to donate Villa Bozio to Lubavitch. Camp Gan Israel has been there ever since.

Six Decades of Campeggio Gan Israel Italia

By now, generations of Jewish children have spent their summers at the place they all simply call Camaiore. Eventually, Garelik’s son-in-law and daughter, Rabbi Avraham and Rivkah Hazan, took over the helm, and today their son, Rabbi Levi Hazan, runs the camp, which attracts about 120 children each summer from throughout Italy and Europe.

A lot has changed since Lipchitz lived and worked there, but much hasn’t. The master’s bedroom at the top of the house, with its little window opening up to the grandest view in the region, is filled with bunk beds. The entire ground level that had been his studio has since been transformed into an appropriate camp space. The food served in the dining room—ragu with pasta; fresh focaccia; olives, tomatoes and grapes that have grown on the sloping property for centuries—remains much the same, even being prepared by the same cook, Loredana, who has lived on premises with her family since before anyone can remember.

The lilting name Camaiore draws smiles and warm memories from its former denizens, evoking in them recollections of a simpler time.

“It was a different era,” recalls Amy Tesciuba, 50, of Rome, whose first summer at Camaiore was as an 8- or 9-year-old in the late 1970s. “For us, it was the first time we were away from home, in this villa in the mountains, it was old but we loved it. It was exciting.”

Back then Camaiore didn’t have a telephone, and so Tesciuba and his fellow campers would have to hike to town to call their parents from a local bar. A few summers later, a telephone line was finally installed at the villa, but the crowd at the phone meant campers couldn’t cry to their parents if they didn’t want anyone to see. But Tesciuba looks back fondly at those primitive days.

“We’d hear late night stories about demons, wake up to Jewish music,” he recalls. “There was netilat yadayim and prayers in the morning, doing a full Shabbat; it was very formative.”

As a boy growing up in Rome, Tesciuba attended Chabad's Talmud Torah but did not go to a Jewish school until high school, yet his informal camp education was so powerful that he found himself more Judaically knowledgeable than many kids his age who did. Once old enough, he returned to Camaiore for three summers as a counselor.

“The experience stays with you,” he says. “It grows with the person.”

When during their 1970 interview Krents asked Lipchitz how his being a Jew had made a difference in his life, Lipchitz laughed and responded, in Yiddish, “Siz shver tzu zein a yid—it’s difficult to be a Jew.” But the truth was that Jacques Lipchitz was a proud Jew, who bore the title gladly and worked hard to fulfill its demands. Recalling the anti-Semitism he had faced throughout his career, he remembered one non-Jewish critic in Paris writing: “But Lipchitz, that’s not sculpture, that’s Talmudism.”

“I liked it very much,” Lipchitz said. “It was a compliment.”

That same sense of warmth, Jewish pride and excitement, says Garelik, was precisely what Camp Gan Israel had been created to perpetuate, back in the traumatic post-Holocaust years and no less today.

“They thought that world was dead, and camp showed that it wasn’t,” reflects Garelik. “Children could be excited about their Jewishness today. It’s not a burden, it’s fun and inspiring; lucky you.”

Photos by Batsheva Helena Goldreich for Chabad.org.

![“There was [hand-washing] and prayers in the morning, doing a full Shabbat," recalls Amy Tesciuba, 50, of Rome, who spent many summers at Camaiore as a camper and then counselor. "It was very formative.” (Photo: Batsheva Helena Goldreich for Chabad.org) “There was [hand-washing] and prayers in the morning, doing a full Shabbat," recalls Amy Tesciuba, 50, of Rome, who spent many summers at Camaiore as a camper and then counselor. "It was very formative.” (Photo: Batsheva Helena Goldreich for Chabad.org)](https://w2.chabad.org/media/images/1061/sxJs10613531.jpg?_i=_n504BC99DD0473598AAE3BCDC5D75568D)

Join the Discussion