It is a story taken almost straight out of Hollywood.

A young Lithuanian rabbi arrives in a “Wild West” frontier town, some 7,000 miles from his home and his family, with only a Torah scroll and a few sparse belongings in his possession. Four generations later, his great-great-grandson returns to help bring Purim to his forbear’s city.

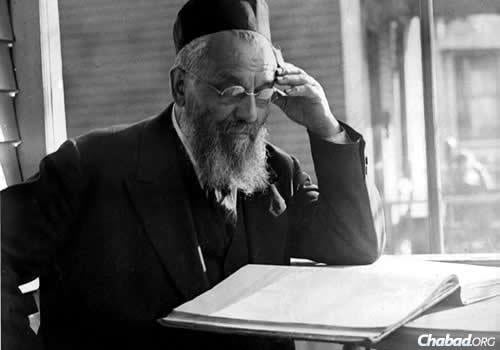

The rabbi was Rabbi Benjamin Papermaster.

As his third-oldest son Isadore Papermaster would later recount in a lengthy letter about his father’s life: “How and why a young man, reared and trained for the rabbinate in the most Orthodox Lithuanian Jewish community of Kovno, under the guidance of the then famous Rabbi Yitzch[ak] Elchanan [Spektor, the chief rabbi of Kovno], was transported to the vast open prairies of North Dakota in 1890 and remained there approximately 45 years of his life in the service of his calling and his people” is a story of Jewish tenacity in America.

Born in November of 1860, the seventh of nine children to Nissen and Etel Papermeister of Anolova, Lithuania, Papermaster studied in the famed Slobodka Yeshiva. When the Jewish community of Fargo, N.D., reached out to Spektor, the esteemed rabbi looked to one person: Papermaster. Trained not only as a rabbi but also as a shochet (a ritual slaughterer) and mohel (a circumciser), the recently married Papermaster was ideally suited for the position far from the Jewish establishment.

Papermaster arrived in Fargo in late 1890. There, he found a group of 15 Jewish settlers and their families who were tenaciously trying to settle the windswept prairie. The local Jews, however, were uninterested in the Eastern European rabbi and more concerned with farming the often harsh environment, in addition to assimilating into their newfound American culture.

Despite the pleas of family in New York to abandon North Dakota, Papermaster felt that he was tasked with a holy mission to serve the community.

A few months after his arrival, the rabbi learned of the tragic passing of his wife, Ethel, back in Lithuania. Nevertheless, he felt he could not leave his post.

Isadore would later write: “One thing he was certain of ... that his future was bound up with this country to which he had just come, and he began to look about for the possibility of making change.”

Arrangements were made for his four young sons, the eldest only 8 and the youngest just 1, to come to America.

Not long afterwards, Papermaster relocated to Grand Forks—75 miles north of Fargo and home to some 60 Jewish families—where the Jews were far more traditional in their practice.

The rabbi later remarried Anna (Chaya) Leviton; they had nine children together.

‘The Guiding Spirit’

Community members would later recount the early tensions between the young Lithuanian rabbi and a congregation that was largely Chassidic in origin. Their customs and traditions differed from his own; even their language was not entirely the same. Coming largely from “Russia”—Galicia and Western Ukraine—many of the local Jews spoke with the earthier southern dialect, while Papermaster spoke with the clipped northern Yiddish of Lithuania.

Isadore recalls one particular episode his father recounted with amusement, which was indicative of this cultural divide.

Attending the Passover seder at the home of a host family, Papermaster took a place by the table, fully expecting the head of the household, Nathan Greenberg, to lead.

Some time passed; Papermaster noticed those gathered anxiously whispering to each other. Turning to his host, he asked what they were waiting for.

“Well, we are waiting for you, as the rabbi, to conduct the seder service,” went the reply.

“In that case,” Papermaster countered, “let us set the table.” Pulling up a chair, he waited for everyone to be seated. Then, a new issue arose. His guests expected him to don the white robe and fur hat of a Chassidic rebbe. Papermaster would have none of it; after some negotiation, the seder began in earnest.

Word quickly spread through the town that the new rabbi was leading a seder at the Greenbergs, attracting throngs of community members who wished to see it for themselves.

“The younger people,” Isadore recalls, “were delighted,” while the older generation grumbled that “the Litvak” (the Lithuanian) would destroy Judaism in the community.

Always pragmatic, Papermaster realized that he would need to adapt to some of the Chassidic customs of his community, as well as to reach out to those who were not nearly as observant, and far from traditional Judaism of any kind.

As he related in his speech the next day, he had promised Rabbi Spektor to bring Judaism to the community where he settled. While his commitment to biblical, talmudic and rabbinic decrees would remain steadfast and strong, he would do his utmost to “reach and preach the Jewish way of life as he understood it, and make it available to all Jews who came under his jurisdiction.”

“I may say without fear of contradiction,” Isadore later wrote, “that this principle was the guiding spirit of his entire career.”

Papermaster would remain in North Dakota for the rest of his life. Until his passing on Sept. 24, 1934, he traveled to outlying Jewish communities in the state’s various small settlements, officiating at weddings, circumcisions and funerals.

‘Larger-Than-Life Story’

In March 2015, Some 80 years after Papermaster’s passing, his great-great-grandson Rabbi Menachem Orenstein, 24, returned to North Dakota.

Orenstein, who along with his brothers is the first generation of Papermaster’s descendants to be ordained as a rabbi, said he was excited about the chance to explore his great-great-grandfather’s history.

“Growing up, the idea that we came from this rabbi who served as the chief rabbi of North Dakota was this larger-than-life story we heard,” he related.

Orenstein first came to North Dakota as “Roving Rabbi” in 2012 to help Rabbi Yonah Grossman, co-director of the Chabad Jewish Center of North Dakota in Fargo, the sole Chabad-Lubavitch emissary in the state. The experience inspired Orenstein to look further into his family’s history. Returning to the state once more for a whirlwind Purim-day tour that would bring him to Fargo, Bismarck and Grand Forks, Orenstein was excited to dig a little deeper than before.

“He was such a unique person,” said Orenstein. “To dedicate your life to Jews in such a far-flung community then, you don’t often hear stories like that.”

Orenstein wasn’t the only one enthusiastic about visiting North Dakota. Resident community members took note as well.

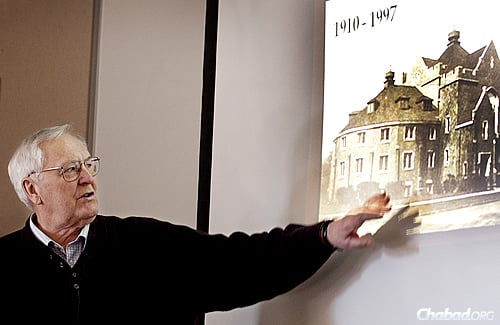

Kenneth Dawes, 78, a native of Grand Forks and a retired professor at the University of North Dakota, grew up in a home once owned by the rabbi. In fact, one of the courses he taught is titled “Rabbi Benjamin Papermaster and the Jewish Community in Early Grand Forks.”

According to Dawes, the Jewish community of Grand Forks reached its zenith during the early 20th century. After World War II, however, as young Jews were attracted to business opportunities elsewhere and the promise of stronger communal life in cities like Minneapolis-St. Paul and Chicago, Grand Fork’s Jewish population began to dwindle.

Despite being born shortly after Papermaster’s passing, Dawes recalled the aura of “the pioneer rabbi in the heart of North Dakota,” which lingered within the community.

Not only that, during the Great Depression Dawes’ parents were in need of a home for their growing family. Approaching Papermaster about an apartment he owned, Dawes’ mother was hesitant to mention the size of her family.

“We were five children at that time,” said Dawes. “She was worried he wouldn’t want to rent to such a large family.”

The rabbi’s remark, however, immediately set her at ease. “ ‘Children,’ ” Dawes remembered his mother relating, “‘have to live, too.’ ”

So impressed was Dawes’ mother by the rabbi’s response that for years to come, she would recount it to her family as an example of his modest and loving nature.

As to Orenstein’s visit, Dawes takes interest in the continuity of the family legacy. “His great-great-grandfather’s memory is one that has gone down in the memory of the history of Grand Forks,” stated Dawes.

Orenstein was of like mind: “I’m fascinated by my great-great-grandfather’s history. But on this trip, I see it as something far more powerful: By traveling to North Dakota, by coming here to help spread Jewish knowledge for the holiday of Purim, I’m perpetuating his legacy. This is what he would want.”

Join the Discussion