Just before midnight on the evening of Jan. 27, 1949, seven agents of the MGB—as the KGB was known at the time—arrived at the central Moscow apartment of the renowned Yiddish poet and playwright Peretz Markish and arrested him. The arrest did not come as a surprise to the 54-year-old Markish; for a month prior, he had been followed by secret police, with agents even posted near his apartment.

“Our minister just wants to have a talk with your husband,” the arresting agents told the writer’s wife, Esther. She would never see him again.1

Markish was not the only one. Beginning in December of 1948, 15 Jewish intellectuals, all of whom had been associated in one way or another with the Jewish Anti-Fascist Committee (JAC), were rounded up and arrested—a part of Stalin’s anti-Jewish campaign that began after the end of the Second World War and culminated with the 1953 Doctors’ Plot. The JAC had been set up during the early months of the war to help rally Jewish support for the Soviet cause in Russia and abroad, as well as raise much-needed American funds for the war effort. It became a near de facto communal representative of Soviet Jewry, headed by legendary Yiddish actor and theater director Solomon Mikhoels (born in Dvinsk as Shloime Vovsi).

But now the war was over, and Stalin had no need for influential Jews with a platform. So, on Jan. 12, 1948, he had Mikhoels killed in Minsk, the cold-blooded murder made to look like a car accident. By November of that year, Communist Party leadership ordered the disbanding of the JAC, stating that “this committee is a center of anti-Soviet propaganda and regularly submits anti-Soviet information to organs of foreign intelligence.”2

Nobody was fooled by the circumstances of Mikhoels’ death, and as the climate for Jews in the Soviet Union grew rapidly worse, those involved with the JAC felt their time was running out.

“Markish lost all hope,” his widow wrote in her memoirs. “He realized the end was near, that it was now only a question of time—days or, at best, months.”3

News of Markish and other Jewish literary figures’ arrests could not be kept quiet for long. Some, like Markish, were very well-known outside of the Soviet Union, and when they suddenly went silent, Jews around the world wanted to know why.

“Soviet Ambassador to the United States Ivan Panvushkin was requested today to verify with the Moscow government reports current here for some time that a number of leading Jewish writers in the U.S.S.R. have ‘disappeared’ without trace,” went a Jewish Telegraph Agency news bulletin dated July 14, 1949. “Among the writers reported to have vanished are [Yiddish poet] Itzik Feffer, who several years ago visited the United States as representative of the now-dissolved Jewish Anti-Fascist Committee of Moscow. Other writers whose fate is unknown include David Bergelson, prominent novelist; Peretz Markish, well-known poet and playwright … and others.”

It was these reports—appearing at the time in Yiddish newspapers—that reached Rebbetzin Chana Schneerson in Brooklyn, N.Y. The mother of the Lubavitcher Rebbe—Rabbi Menachem M. Schneerson, of righteous memory—Rebbetzin Chana had herself arrived safely in the United States just two years earlier, having illegally crossed the Russian-Polish border and traveled via Krakow, Pocking, Munich and Frankfurt to Paris, where she was met by her son, the future Rebbe. The Rebbe was by then living in New York and had flown to France to escort his mother back to the United States; the two had not seen each other in 20 years. They arrived together on American shores in the summer of 1947.

A few months later, on the day after Rosh Hashanah, Rebbetzin Chana began recording her memoirs:

I am not a writer, nor the daughter of a writer. My desire is to record some memories of the final years of my husband, of blessed memory. I am unsure whether I will succeed. Firstly, will I be able to put all my recollections into writing? And secondly, will I have the peace of mind needed for such a task?4

She succeeded, despite her doubts, recording her painful personal memories while simultaneously painting a larger portrait of the state of Russian Jewry at the time. In clear, simple but often searing words, she powerfully communicates the heavy price paid by Jews in the Soviet Union. Yet from amid the sadness and fear, bright spots emerge as well—stories of the Jewish spark emanating from unexpected places.

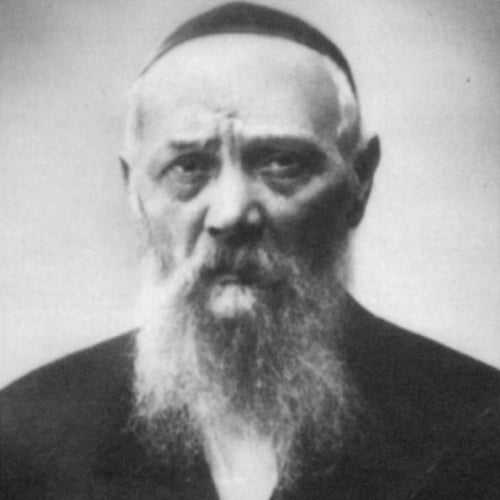

As the wife of one the most prominent rabbis in the Soviet Union at the time, chief rabbi of Dnepropetrovsk Rabbi Levi Yitzchak Schneerson, Rebbetzin Chana had witnessed things few others had. She writes about the Jewish building superintendent whose job it was to inform on the couple to the NKVD (a precursor to the MGB, itself a precursor to the KGB; while the name changed, its work didn’t), yet when asked, participated as the 10th man in a secret chuppah ceremony held at their home in the middle of the night. She also recalls the Communist factory boss who requested that the rabbi secretly circumcise his son while he was out of town. And then there is the story of the internationally known poet, the handsome and celebrated Peretz Markish.5

“Today I read in the newspaper that the writer, Peretz Markish, has been exiled to some unknown location in the Soviet Union,” wrote Rebbetzin Chana in 1949. Her husband had been arrested in 1939 and eventually sentenced to exile in the barren solitude of Kazakhstan, where he was later joined by his wife, and where he passed away in 1944. Hearing of Markish’s arrest and (falsely) reported exile, she did not seem shocked by the rumors; she was all too familiar with the Stalinist reality. But it did trigger a memory: “This news also reminded me of an episode in the life of my husband, of blessed memory.”

A Rebel and Point Man

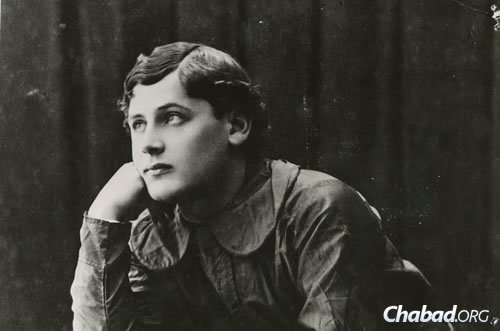

Peretz Markish was born in 1895 in the Ukrainian shtetl of Polonnoye. His parents, Dovid and Chaya, were strictly observant, and his father was a melamed in the cheder, teaching young Jewish boys how to read Hebrew. Young Peretz’s early education also took place in the cheder, and until his Bar Mitzvah he sang in a synagogue choir in Berdichev—a heavily Jewish city his family moved to at some point.6 His natural tendencies were rebellious, and, like so many of his contemporaries, he was drawn to the revolutionary spirit of the time. By age 15, he was writing poetry in Yiddish; he was published for the first time in 1917.7

“A man of stormy temperament, who instinctively loathed all that was static and conventional, he was enchanted by the very idea of launching an assault against the fortress of conservatism—a predisposition manifested also in the titles he gave his collections of poems, titles like Stam [Just Like That] or Hefker [Carefree],” writes historian Yehoshua Gilboa.8

Yet for all of his love of the unsettled and new, “Markish nevertheless appears at times … unable to discard his deep roots in Jewish life and tradition.”

Indeed, one of his most prominent early works is the tragic poem Die Kupeh, “The Heap”—the name referring to the heaps of the slain—which speaks bitterly of the brutal pogroms suffered by the Jews of Ukraine in 1919. Wrote Markish:

For you, the slain of the Ukraine that fill the land, the slaughtered that lie in a heap in Horodishch on the Dnieper’s banks—I say Kaddish!9

Markish left the Soviet Union in 1921, spending time in Warsaw and traveling the world, returning in 1929. By that time, Stalin was already consolidating power; he no longer had a need for unbounded revolutionary fervor, nor, for that matter, anything else he could not control. True, Markish had already written many revolutionary works, yet Communist reviewers denounced the tenderness with which he overtly continued to treat many Jewish themes.

“He was charged with idealizing a life that was outmoded, reactionary, pious, patriarchal, whereas ‘Markish might have been expected finally to discard his former nationalistic idols,’ ” writes Gilboa, quoting negative Soviet reviewers. “He was censured … for the manner in which he depicts a group of Jews who happen to get together at an inn and ‘snatch’ a communal prayer [khap a minyan], or his description of a seder conducted in a regal manner … ”

“We do not find a single line that would indicate the author’s negative attitude to this patriarchalism,” wrote M. Kamenstein about Markish in Kharkov’s militantly anti-religious Shtern newspaper.10

With pressure to conform to the party’s vision, Markish fell in line, at least on the surface. New demands were being placed on him and other authors. They were to depict the successful construction of a new world—the hoped-for future as if it were today. Although Markish expressed disillusionment to his wife following a 1934 visit to Birobidzhan, Stalin’s Jewish autonomous republic, he nevertheless published an ode to the failed project a year later.11 Markish’s profile grew as his work became more and more kosher in Soviet terms, but, predictably, his work’s quality suffered. Elected to head a committee in the Soviet Writers’ Congress Yiddish section, he was soon living with his family in a large apartment in an upscale building.12 In 1939, Markish received the Order of Lenin, becoming the first and only Yiddish writer to receive the honor in the history of the Soviet Union.

It was in 1937—at the high point of both his fame and obedience—that Markish got news of his father Dovid’s death in Dnepropetrovsk. And it’s here that the story returns to Rebbetzin Chana’s narrative.

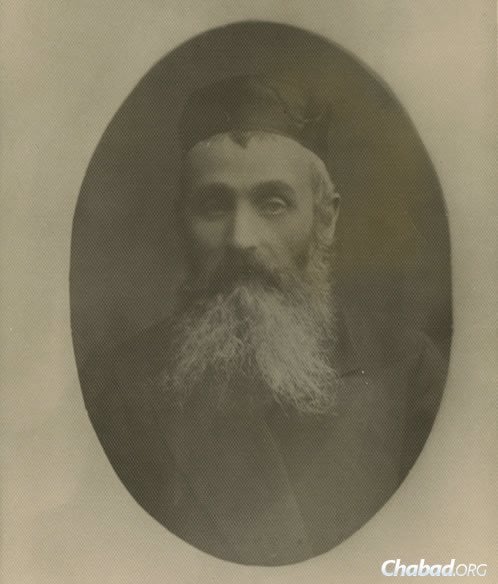

“His father was Torah-observant, and was a regular at our home,” she wrote. “Prior to his passing he left instructions that his burial be conducted in accordance with all of Rav Schneerson’s directives.”

Hearing the news, Markish and his sister quietly made their way to Dnepropetrovsk.

A Clandestine Burial

By 1937, it was too late. Stalin was not only in control, but had created a world where he was everything to everyone, his domination of all facets of life a direct reflection of his orthodox Marxist-Leninist beliefs. If politics was history, then perceived deviation from Communist Party policy was a crime against history itself. What was the value of one life or a million lives when seen in the broad context of humanity’s forward march? It was in this climate that began Stalin’s purges, the wholesale arrest of millions of individuals on a variety of charges that had little relationship to reality. So prevalent were the arrests that people slept with their suitcases packed and ready near their bed.

And that’s when Peretz Markish arrived in Dnepropetrovsk to bury his bearded religious father. In utter secrecy, the poet sent his two sisters—one a Communist Party member who served as his secretary and had traveled with him from Moscow, and the other who lived in Dnepropetrovsk, and with whom their father had lived—with a message for the rabbi.

“He wanted my husband to know that, although he couldn’t meet with him personally, the Rav should be aware that regardless of Markish’s personal ideology and prominent position, he held Rabbi Schneerson in the highest esteem and related to him with the greatest personal respect. This was based on his own experience and on his father’s frequent letters to him, which made a deep impression on him,” remembers Rebbetzin Chana.

Continuing to communicate everything regarding his father through his sister, he asked that everything be kept as quiet as possible. “All details of the burial, which was also in a favorable plot, were performed in the finest possible manner relative to the conditions of that time.”

With the funeral over, the writer and his sister prepared to return to Moscow. He had respected his father’s wishes during an exceedingly dangerous time, even communicating with a rabbi by the last name of Schneerson—which, judging by secret police interrogation transcripts, was more than enough reason to arrest someone. Yet there was something more the wealthy Markish chose to do, obviously of his own volition.

Before they left, writes Rebbetzin Chana, “the family donated large sums for the city’s clandestine Torah schools for children and the like, which were conducted at great personal peril to those involved.”

Markish left town the night after the funeral. No one else in Dnepropetrovsk knew anything of the visit.

‘Remain One Entity’

The war years and relative freedom of expression allowed at the time by Stalin proved to be a boon to Markish’s work, as he began returning to the “nationalist” themes he had touched on earlier on in his career.

“Do not part from your rifle, Jewish soldier,” wrote Markish in a poem titled To the Jewish Fighter, “just as your forefathers have never parted from the Sefer Torah.” Gilboa noted that in the same poem: “He reminds the Jewish fighter of the Ten Commandments handed down on Mount Sinai, which have endowed the world with moral values, and which Jews still stand by, though their throats be butchered and their mouths incinerated.”

“Avraham Sutzkever wrote about Markish, and he describes him as someone who was powerfully involved with Jewish life,” explained Ruth Wisse, professor of Yiddish Literature and Comparative Literature at Harvard University and a senior fellow at the Tikvah Fund. “It seems almost characteristic of him that the worse things got during the war, the more Jewish he became.”

Overlooked sometimes in the modern view of Markish and some of his contemporaries was the deep impact they had on a Jewish people who had been cut off from traditional religious life and learning. With words, they recreated a world that had in large part been uprooted, offering generations of Soviet Jews a glimpse of what authentic Judaism resembled.

“All of these authors had a huge effect on Soviet Jewish consciousness,” said Rabbi Boruch Gorin, chief editor of Moscow’s Knizhniki Publishing House and the editor in chief of Lechaim magazine.13 “After the war, Stalin quickly understood that Jews cannot become Soviet citizens totally, so Yiddish had to go. Even those thoroughly Soviet Yiddish writers had to go.”

It was a terrible end that they would face.

“Hitler wanted to destroy us physically,” Markish told a friend following Mikhoels’ murder. “Stalin wants to do it spiritually.”14

After their arrests, the Jewish Anti-Fascist Committee activists were cruelly interrogated and tortured, with Markish’s treatment among the worst. He was interrogated two or three times a day, questioned all day, and then again from 11:30 p.m. until 5 the next morning, 96 times in all.15 Under torture at the hands of one of the MGB’s most sadistic officers, Markish signed a confession of guilt (he was accused of treason), effectively signing his own death sentence. On Aug. 12, 1952, after a sham secret trial at which they were all found guilty, 13 of the 15 defendants were executed with a bullet to the back of the head—a crime that has since become known as the Night of the Murdered Poets.16

Rabbi Levi Yitzchak Schneerson was frail and ill when he passed away in exile in Almaty, Kazakhstan, on Aug. 9, 1944, where he is buried. The date on the Jewish calendar of his passing is Chof Av, the 20th day of the month of Av. Markish’s yahrtzeit, along with the other victims of the Night of the Murdered Poets, is just one day later, on 21 Av. Markish’s KGB file identifies his “burial” place as a mass grave at the Donskoye cemetery in Moscow.17 The religious Lubavitcher rabbi and the Soviet Jewish poet—one a member of a then-disappearing breed of Russian Jew and the other thought to be thoroughly modern and secular—connected in life and in death.

Markish himself might have said it best. At a post-war memorial for the martyred Jews of Poland, one Yiddish writer noted that the gathering showed the “friendship of the Jewish peoples.”

“There are no two Jewish peoples,” Markish responded. “The Jewish nation is one. Just as a heart cannot be cut up and divided, similarly one cannot split up the Jewish people … Everywhere, we are and shall remain one entity.”18

Images of Peretz Markish, his family, and artifacts are courtesy of the Blavatnik Archive.

Join the Discussion