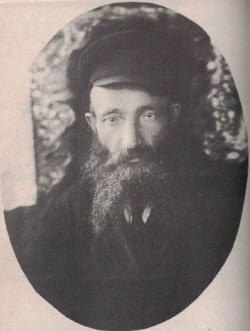

In the early 1900s, Zeide Eliezer and Bubbe Rochel Leah Paltiel lived with their five children in a village in Belarus called Zhudilovo, which was under the rule of the Russian czar. The nearby forest was the source of their livelihood, as Zeide Eliezer was a logger. He rented land from the Russian owner, and he and his sons felled trees and floated the logs down the Dnieper River in long barges to the big cities, where they would be used by builders. My father, Berel, remembers his oldest brother, Yaakov, sometimes seating him on the saddle of his horse and giving him rides between the woods and home. Thus, the sound of the saw, the smell of freshly cut wood, and the tall trees of the forest were as natural to little Berel as the sights, sounds and smells of his own home.

Since Eliezer and his older sons were in the business of cutting trees, and wood was plentifully available to them, they decided to build an addition to their small home. At that time, Yaakov was studying at the yeshivah of the Rebbe Rashab, Rabbi Sholom DovBer of Lubavitch, so Zeide Eliezer sent a message to Yaakov to ask the rebbe for a blessing to build the addition. Yaakov relayed the rebbe’s answer to his father: building two additional rooms to his home would be a blessed endeavor, and he should proceed with his plan.

The head of the Duma (village governing council) in my grandparents’ village was a wicked man named Ivan Stepanovich. Like the evil Haman, he was always on the lookout for some excuse to harm the Jews, particularly to pin some crime on Zeide Eliezer, whom he considered a “rich Jew.”Should he stop building altogether?

The truth is, besides the little house in which he and his family lived, Zeide had almost no material possessions, so why did Stepanovich resent him? Perhaps because when Stepanovich passed by their small home on a Friday night, he heard the family singing; whenever he entered Zeide’s home, he saw the family sitting at their festive meal as though they were princes and princesses. In short, the little wooden house was filled with learning and love and joy—the kind of love and joy that no money can buy.

When Stepanovich noticed that Eliezer and his sons were building an addition to their house, he devised a plan to endanger them, and perhaps even incite a pogrom! As head of the village governing council, Stepanovich decided to create a new law in the village. Going forward, whoever built a new house, or remodeled his existing house in any way, needed to apply for a permit to do the work. Not surprisingly, the permit was to be granted by none other than “His Excellency,” the village Duma head himself. The new rule was voted on and passed by the village elders, so that now altering one’s home without a permit was considered a crime.

An official letter was delivered to Eliezer Paltiel from the village of Zhudilovo, ordering him to stop building immediately and to appear in court in the city of Pochep on an appointed day, as he was charged with breaking the new permit law.

Zeide Eliezer dispatched an urgent message to the rebbe asking how he should proceed, because it was clear to him that the permit issue could turn into a very dangerous situation for his family, as well as for other Jews in the surrounding district. Should he stop building altogether? How should he handle the court date? Zeide Eliezer beseeched the Rebbe Rashab for his advice and blessing.

The answer they received astounded the family. The rebbe simply told Zeide Eliezer and his sons to continue building without fear, as G‑d’s blessing was with them.

In the meantime, Ivan Stepanovich prepared his case against Zeide Eliezer.

Time seems to have a tendency to fly when you want it to go slowly, and indeed Zeide Eliezer’s court date approached rather quickly.

On the day before the trial, Stepanovich came to Zeide Eliezer’s house, a large sheaf of papers in his hand.

“I am in possession of a list of all your crimes, Jew Paltiel,” he said, waving the stack of papers in Zeide’s face. Then he thrust his package under his arm, puffed out his chest, put his hands on his hips and stood waiting for Zeide’s reaction.

Zeide Eliezer stood motionless for a moment, facing Stepanovich and considering what to reply to his accuser. It was clear to Zeide that this enemy of the Jews had a pogrom in mind, and would not be satisfied to simply forbid the addition of two rooms to a little wooden house. Then he replied calmly, “I hope His Excellency knows that the work my sons and I are doing in our house was started before the law was enacted. The law shouldn’t apply to renovations that were begun before there was a law. Should men be held responsible for committing crimes that were not crimes when they were done, and only later became illegal?”

While Zeide talked, Ivan Stepanovich’s face turned pink, then red, then deep crimson. His pulled himself up to his full five feet, and with his arms bent, hands grasping his waist, he looked as though he were about to dance a kazatzka. “Your end is near, Jew Paltiel!” His Excellency screeched. “I know your Talmud teaches you how to argue, but no argument will help you this time. You will pay! And not only a fine,” he wagged his finger ominously at Zeide. “You will lose your house and your business, too.” He waved the sheaf of papers tauntingly under Zeide Eliezer’s nose.

Bubbe Rochel Leah was standing in the kitchen peeling potatoes for soup, listening to the exchange between her husband and the village head, while tears streamed down her face, half-covered by the kerchief that sat low on her forehead. Her little son Berel, who was then two years old, was holding on to his mother’s skirt, his eyes raised to her tear-stained face. He didn’t understand why she was crying, nor did he understand his father’s conversation with the man wearing brass buttons on his long fancy coat, whose whiskers pointed to both sides of the village.

Berel’s sister, 11-year-old Manya, had gone with her friends to the train station to watch the trains come and go. Trains were a new phenomenon then, and therefore an interesting spectacle to all the area’s children. With the roar of its engine, its wheels screeching against iron rails, the Pochep-bound train pulled into the station.

Ivan Stepanovich stood on the platform, looking forward to Eliezer Paltiel’s trial the next day. This time, he felt certain he would be rid of the rich Jew once and for all. Afterward, the Jew’s guilt could easily be used to incite a pogrom that would begin first in his village and then spread to the surrounding villages.

Wanting to appear above others, His Excellency did not board the train when the less important passengers did. After the conductor called out, “All aboard, all aboard,” Stepanovich stood chatting with the stationmaster. Only when the train began to move, slowly at first, did he jump on the bottom step, expecting to take the successive steps and land neatly in the moving car. But his long coat with the brass buttons got caught in a spoke of an iron wheel that was rolling faster and faster on its rail.

Manya ran home out of breath, not knowing if she should feel sad that a fatal accident had occurred, or be glad that this man—this Haman, who she knew wanted to harm her father and all the area’s Jews—had been dragged by a moving wheel to his death under the train. She sprinted into the house screaming as loudly as she could, “Er iz mer nit doh, er iz mer nit doh!” (“He is no more, he is no more!”)

At Ivan Stepanovich’s funeral, “You fool! You fool!”his wife walked behind her husband’s coffin, wringing her hands and wailing, “I told you not to start up with the Jews. I told you to leave the Jew alone. You know their G‑d is powerful. You fool! You fool! You fool!”

The new village head did not follow Stepanovich’s example. He was an honest man who conducted himself with proper decorum and common sense, and he never bothered Zeide Eliezer. It was obvious to him that his predecessor had created a new law and then brought charges against Zeide Eliezer for no other reason than his eagerness to harm a Jew.

So, with the rebbe’s blessing, Zeide Eliezer and his sons added two rooms to their home, and the evil plot of Stepanovich was foiled.

This true story was told to me by my father, Reb Berel Paltiel, the youngest son of Reb Eliezer and Rochel Leah Paltiel.

Join the Discussion