At the same time, Rabbi Moshe ben Maimon acquired world renown as a Talmudist of unusual knowledge and acumen. Scholars and Rabbis from all over the world sent him their questions and queries in Judaic law (Halachah). At the comparatively young age of forty-two, the Jewish community of Cairo appointed him as their Chief Rabbi, one of the most prestigious offices of the Jewish world at that time. Even before his formal appointment, his exceptional Torah scholarship and eminent personality made him the spiritual leader of Egyptian Jewry. When Rabbi Maimon's family settled in Egypt, the Karaites were in the majority and were more influential than those adhering to traditional Judaism. There was the danger that the large Jewish population of Egypt would be lost to Karaism. It was only a man of such great stature and authority as the Rambam who could stem the tide and eventually reverse it to traditional Judaism. In addition to his professional career as a physician and his voluntary activities as Chief Rabbi of the Jewish community, this great man still found time to study and to write masterful works on all branches of the Talmud, philosophy and medicine.

Commentary on the Mishnah

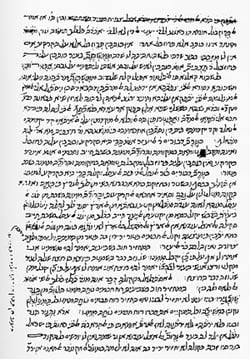

Rambam made three major contributions in the field of Jewish law and Talmudic study through his literary works: Commentary on the Mishnah, Sefer HaMitzvot, and Mishneh Torah. The earliest of these monumental works was his Commentary on the Mishnah, popularly known as Sefer HaMaor (The Luminary). He began this work at the age of twenty-three, while on his way fleeing the Mohammedan persecutions, and completed it seven years later in Fostad. "I was working on this Commentary under the most arduous conditions... as we were driven from place to place... while traveling by land or crossing the stormy sea," he writes at the conclusion of this work. His clear, methodical and analytical mind and his remarkable ability to arrange the material systematically is already evident in this early work. The Commentary offers brief explanations for each Mishnah, in the six "Orders" which comprise the Mishnah, elucidating the meaning of every dictum which is not perfectly clear from the text. These explanations are generally gleaned from the vast material and the lengthy discussions of the Talmud, and where no interpretation is found in the Talmud, Rambam gives those of his predecessors, the Gaonim, or his own. Wherever necessary, he includes in his commentary scientific information showing thereby that the Sages of the Talmud were well-versed in all spheres of secular knowledge. Besides its expository value, the Commentary has an added asset for the practical application of the law. It delineates the final halachic decision from among the various opinions mentioned in the Mishnah.

Rambam composed an elaborate Introduction to the Commentary in which he discusses various fundamental concepts of the Jewish religion, such as prophecy, revelation and tradition, the development and the principles of the Oral Law1, and the like. He also wrote individual introductions to all difficult sections of the Mishnah and to all complicated subjects treated in the Mishnah, clearly elucidating the pertinent principles underlying the laws and furnishing a concise summary of all the relevant halachic concepts. All this precedes the detailed commentary which explains the meaning of the Mishnaic text.

Thirteen Principles of Faith

One of the most famous and significant of Rambam's introductions is his preface to the tenth chapter of the tractate Sanhedrin. There he formulates the "Thirteen Principles of the Jewish Faith." These fundamental principles of Judaism have been incorporated into the liturgy of many Jewish communities, who recite them at the beginning of the daily morning prayer, in poetical form (Yigdal), and at the end, in prose form - Ani Maamin.

The first five of these cardinal principles deal with the existence of G‑d the Creator, His Oneness, His incorporeality, His eternity, and the principle that all prayer and worship are due G‑d alone. The next four principles pertain to prophecy in general, to the unique, preeminent level of Moses prophecy, to the Divine origin of the Torah and to its immutability. Principle ten and eleven affirm G‑d's omniscience and the certainty of reward and punishment for observance or transgression of the commandments. The final two principles deal with the Messianic redemption and the resurrection of the dead.

Equally famous is Rambam's introduction to Pirkei Avot, the Talmudic tractate which deals with ethical behavior. Although it is only an introduction to Pirkei Avot and but a small part of his Commentary on the Mishnah, it is, nevertheless, a highly significant ethical treatise in its own right. Popularly known as Shemoneh Perakim (Eight Chapters), this treatise has been translated into many languages. In it Rabbi Moshe ben Maimon offers a systematic presentation of the foundations of Jewish ethics, and discusses such basic Jewish concepts as the nature of the soul, its maladies and cures, immortality, freedom of will, freedom of choice and Divine foreknowledge, and similar topics touched upon in Pirkei Avot.

His Talmudic genius is especially evident in his Introduction and Commentary to Seder Taharot (Order of Purity), which comprises twelve tractates of the most complicated laws of purity and impurity. Rambam's Introduction and Commentary succeeded in making these intricate tractates of Mishnah accessible and readily comprehensible.

The Commentary was written in the Arabic vernacular, the language the masses understood, and called Kiteb El Siraj (The Luminary). Later, successive parts were rendered into Hebrew by various scholars. The popularity of this work can be seen from the fact that it is appended to every complete edition of the Talmud.

Even before he began his Commentary on the Mishnah, i.e., before the age of twenty-three, Rambam was an accomplished author. His first known works were Ma'amar Halbbur, a treatise on the Jewish calendar in which he demonstrates a profound knowledge of astronomy and mathematics, and Beur Millot HaHigayon, a philosophic dissertation on logic, both of which survive in Hebrew translation. He composed also a commentary on almost three entire sedarim (Orders) of the Babylonian Talmud, viz., Moed, Nashim, and Nezikin, as well as on the tractate of Chulin, and wrote a digest of laws on the Jerusalem Talmud similar to that which Rabbi Yitzchak Alfasi wrote on the Babylonian Talmud. Neither of the Talmudic commentaries - with the exception of a few tractates - are extant. The digest of laws which was heretofore never published, and thought to be lost, was recently discovered and published for the first time in 1947 in New York. That he could create all this, still in his teens, under the most trying circumstances, while fleeing from country to country, without having at his disposal all the necessary books is all the more incredible!

Truth does not become more true by virtue of the fact that the entire world agrees with it, nor less so even if the whole world disagrees with it.

Moreh Nevuchim 2:15

Join the Discussion