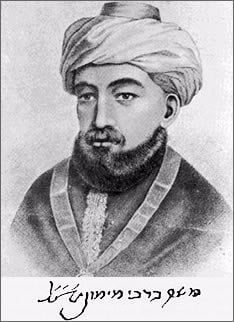

Rambam was born on the fourteenth day of Nissan – the day before Passover – in the year 11351, in Cordova, Spain. He was a descendent of a distinguished and scholarly family tracing its ancestry to Rabbi Yehudah HaNassi, the compiler of the Mishnah, and even further back to the royal house of King David. At the conclusion of his Commentary on the Mishnah – the compilation of the Oral Tradition of the Torah (tractate Uktzin 3:12), Rambam enumerates his ancestry eight generations back, indicating that all were distinguished Dayanim, Rabbis and scholars. His father served as Dayan – a judge in the Jewish court of law – of the Jewish community of Cordova and was famous not only for his vast Torah knowledge, but also for his general scholarship, especially in mathematics and astronomy. Rabbi Maimon himself taught his prodigious son Scripture, Talmud, and every aspect of the Jewish religion and tradition, and provided him also with a multifaceted education and a thorough training in worldly sciences. It was at the suggestion of his father that the young Moshe immersed himself in the study of philosophy and medicine – fields in which he was to later attain world renown.

The young Moshe was barely Bar Mitzvah when the fanatical Almohades conquered Cordova in 1148. These ruthless, savage Muslims tolerated no other religion than their own and offered the Jewish population the choice of conversion to Islam, death, or expulsion from their native land. Thus the Jews were given the excruciating alternative of either surrendering their eternal faith or their very life, or abandoning their homeland where they had lived for many centuries, leaving behind all their possessions, to seek a haven of refuge in a hostile world where they were nowhere welcome. The vast majority of the Jews, among them the Dayan and his family, chose exile and left Cordova. Of those who could not leave, many met a martyr's death, sanctifying the Name of G‑d, and some became insincere converts to Islam, merely outwardly, all the while, secretly, in their hearts and in the privacy of their homes, observing and practicing all the precepts of the Torah, never abandoning their inherited religion.

Rabbi Maimon and his family wandered about from city to city in Southern Spain, without being able to stay in any one place for a long period, for the conquering Almohadian hordes swept all across Southern Spain. After ten years of a nomadic life, they joined a group of fugitives who headed toward North Africa and eventually settled, in 1159, in Fez, then the capital of Morocco. But they were still not destined to enjoy peace and security. After a five year stay in Fez they had to leave because of religious intolerance and persecution. They again became wandering Jews, without a home. By way of Jerusalem and Hebron, the Maimon family made their way to Egypt. The Holy Land, desolate and unpopulated, ravaged by the Crusaders, did not afford them a permanent place of residence. They spent three days in Jerusalem in prayer at the Western Wall, and one day in Hebron praying at the graves of the Patriarchs at the Cave of Machpelah. From there they proceeded to Egypt. In Fostad, near Cairo, the seat of the Caliphate, the family of Rabbi Maimon at last found a haven. Unlike other Muslim countries, the Jews in Egypt, under the tolerant and enlightened rule of the Fatimide caliphs, were granted complete religious and civil freedom. They were allowed to develop their religious, cultural and communal life, as well as to engage in commerce without any restrictions or interference. It was here that Rabbi Moshe was to create the masterworks for which the Jewish people are forever indebted to him.

In Egypt

They had barely settled in their new domicile, and were just beginning to enjoy the long sought life of freedom and peace, when misfortune struck the Maimon family.

A few months after their arrival in Fostad, Rabbi Maimon, the former Dayan of Cordova, passed away. Rabbi Moshe deeply mourned the loss of his great father, who was to him not only a father but also his foremost teacher and most important influence.

Rabbi Maimon wrote a commentary on the Talmud, which his son Rabbi Moshe mentions in his introduction to the Mishnah and which he used as a source in the preparation of his own work2. His younger brother, David, took upon himself the responsibility of providing financial support for the entire family, in order to enable his gifted brother, Moshe, to devote himself to his studies without financial worry. David became a jewel merchant, importing gems and precious stones from India. He succeeded in this business and the family lived very comfortably. Unfortunately, the family was struck again by tragedy with the untimely death of their provider. On a business trip to India, the ship on which David was sailing was caught in a storm, shipwrecked in the Indian Ocean, and David drowned, carrying with him the entire family fortune.

It devolved upon Rabbi Moshe to become the breadwinner of the family. However, as a result of his incessant study and his grief over his brother's death, he became seriously ill. Bedridden for several months, he was unable to provide support for his family. When he finally recovered, he began to practice medicine. Rambam did not deem it proper to obtain monetary benefits or receive financial remuneration from his vast Torah knowledge. Torah should be studied and taught, he maintained, only for the sake of Heaven and not for earning a livelihood.3 Hence he devoted himself to the vocation of medicine. He was so successful in this profession, and in the course of time gained such a reputation, that Grand Vizier Alfadhil, and eventually Sultan Saladin as well, appointed him to be their personal physician.

It is incumbent upon us to love and fear the glorious and awesome G‑d, as it is written, "You shall love the L‑rd your G‑d" (Deut. 6:5), and "You shall fear the L‑rd your G‑d" (Deut. 6:13). How does one attain love and fear of G‑d? When a person reflects upon His great, wondrous deeds and creatures, and from them perceives His infinite, unbounded wisdom, he will immediately be aroused to love, extol and glorify Him, and he will yearn with an exceeding yearning to know the Almighty G‑d... By [further] meditating on these matters he will recoil, awe-stricken, resolving that he is a small, insignificant creature, endowed with limited, meager intelligence, who stands in the presence of the One who is perfect in knowledge...

Mishneh Torah, Yesodei HaTorah, 2:1-2

Join the Discussion