Rabbi Moshe ben Maimon was not only the leading personality in Talmudic and Judaic law of his time, but also the chief exponent of Jewish religious philosophy. After concluding his magnum opus, the Mishneh Torah, Rambam set out to present the religious philosophical views of Judaism. These he elaborated on in his masterly philosophic treatise, Guide for the Perplexed (Moreh Nevuchim), wherein he deals comprehensively with Jewish doctrine and practice from a philosophical point of view.

Guide for the Perplexed

In this work, Rambam provides answers to the perennial questions for which the human mind ever searches: the nature and existence of G‑d, the purpose of Creation, G‑d and His relation to the universe, the meaning of life and human destiny, the origin and underlying reality of evil, free will, Divine Providence and Omniscience, Divine Justice, Revelation, the purpose of the precepts of the Torah, the true way of worshipping G‑d, and many others.

In the countries under Islamic cultural influence, such as Egypt where Rambam lived, where Greek philosophy captured the imagination of the intelligentsia, it became popular also in certain Jewish circles. With the growing interest in the works of the ancient Greek philosopher Aristotle, especially in its Arabic garb and formulation, there arose an apparent conflict between the views of secular philosophy and certain statements and ideas expressed in the Torah and Talmudic literature. For instance, how can G‑d's absolute in-corporeality and spirituality be reconciled with the anthropomorphic, human descriptions of Him in the Bible.

The philosophically oriented Jews, while firmly committed to the principles and practice of Torah Judaism, were troubled and perplexed by the seeming contradiction between reason and faith. Rambam, in his deep-felt concern for the spiritual well-being of his people, recognized the inherent danger to which such a situation might lead. This danger was especially acute among the less educated in Jewish religious thought among whom Aristotelian philosophy threatened to make serious inroads and who, as a result of the apparent inconsistencies between reason and faith, began to waver in their religious commitment.

Rabbi Moshe ben Maimon, well-versed in the teachings of the ancient and contemporary philosophers, therefore, felt himself compelled to compose a systematic presentation and exposition of the fundamental religious-philosophical principles of Judaism, which would answer the questions which agitated the philosophically oriented intellectuals, remove the doubts of the "perplexed" and enable them to continue to adhere to Torah-true Judaism. "My intention," says the Rambam in the introduction to the Guide for the Perplexed, "is to expound Biblical passages which had been impugned, and to elucidate their hidden and true meaning which when well understood, serve as a means to remove the doubts concerning anything taught in Scripture; and, indeed, many difficulties will disappear when that which I am about to explain is taken into consideration."

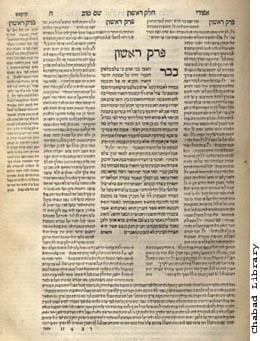

The Guide for the Perplexed was originally written in Arabic with Hebrew characters, and titled Dalalat al-Chairin. No sooner had the work been completed than the author was besieged with requests from various centers of Jewish scholarship for copies of his latest work, and for a Hebrew translation for the benefit of those unfamiliar with the language in which it was written. Within a decade after its appearance, two Hebrew renditions were made, one by Rabbi Shmuel ibn Tibbon and the other by Rabbi Yehudah al Charizi.

Ibn Tibbon's rendition has been accepted as the authoritative one because of its faithfulness in conveying the exact meaning of the author in all its nuances. Ibn Tibbon consulted Rambam through correspondence regarding the meaning or wording of all difficult passages. Rambam himself gave the translation his approbation, calling Ibn Tibbon the most able and fit person to discharge this task. The translation by Al Charizi, although superior as far as beauty of language and elegance of style is concerned, was lacking in precision and exactness of meaning. Rabbi Avraham, Rambam's son, expressed dissatisfaction with Al Charizi's translation because of its inaccuracy1.

Influence of the Guide for the Perplexed

Interest in this philosophical work was not limited to Jewish scholars but it was assiduously studied by thinkers of the non-Jewish world, both Arabic and non-Arabic. Even in Rambam's lifetime, the book was transcribed into Arabic letters and used extensively by Mohammedan scholars. Not long afterwards, a Latin rendition of the Guide for the Perplexed appeared in Europe, followed by Spanish and Italian versions.

At about the middle of the nineteenth century, interest in the work by non-Jewish philosophers was revived as a result of a new translation into French by Solomon Munk. Subsequently, it was translated into almost all European languages. The work wielded great influence on the scholastic philosophers of the Middle Ages, and was extensively quoted by many of them, notably Albertus Magnus, Thomas Aquinas, Duns Scotus and Roger Bacon. Thus, Maimonides occupies a most prominent place in the annals of general theological philosophy.

The Guide for the Perplexed, dealing with abstruse metaphysical concepts, became one of the most commented upon philosophical classics of all time. There are more than thirty commentaries on it in Hebrew by known authors, and many more authors whose identities are unknown. It is interesting to note that some of these commentaries include explanations from the Kabbalistic perspective. This indicates that beneath the philosophical veneer of the Guide for the Perplexed lie Kabbalistic ideas, and by studying it only from the rationalistic-philosophic point of view one does not plumb the depth of its content. This is in accord with the view of those who hold that Rabbi Moshe ben Maimon was not only a Talmudist and philosopher but also a Kabbalist.

During the past 200 years, it has been revealed in Chabad-Lubavitch literature that he was also a mystic steeped in the study and traditions of Kabbalah. In fact, the source of some laws in his Code, Mishneh Torah, are found only in Kabbalistic literature.

Rambam, through this monumental work, laid the foundation for all subsequent Jewish philosophic inquiry known as Chakirah, and stimulated centuries of philosophic Jewish writing. Whether the philosophers accepted his conclusions or not, whether commenting and elaborating on his ideas or criticizing them, each one was influenced to a large degree by his approach and ideas. His writings served as the foundation upon which they continued to build. The Guide for the Perplexed has dominated Chakirah since its appearance down to the present time and exerted a profound and enduring influence on Jewish thought.

As the fame of the Guide for the Perplexed spread, the enthusiastic recognition of the work was countered by vehement opposition on the part of those opposed to the attitudes and principles of philosophy. The struggle between the protagonists of philosophic inquiry and its opponents lasted for decades after the passing of the Rambam, and, unfortunately, at some periods took the form of acrimonious protest and even personal hostility against the intents and character of the holy Rambam.

Join the Discussion