Although current relations between Jews and some Arabic-speaking countries are a bit strained, to say the least, it was not always so. In fact, there was a time when most Jews lived in Arabic-speaking countries, and thus many Jewish books were written in Arabic—or to be more precise, Judeo-Arabic, which was either the Jewish dialect of Arabic or classical Arabic written with Hebrew letters. Most of these works were later translated into Hebrew and other languages, becoming foundational Jewish classics—to the point that many people are unaware that these works were originally written in Arabic.

Here are seven such works:

1. Kitab al-Amanat wa’l-I’tiqadat (Emunot V’deiot—“The Book of Beliefs and Opinions”), by Rabbi Saadiah Gaon

Rabbi Saadiah Gaon (Saadiah ben Joseph Al-Fayyumi) was born in Egypt; served as gaon and head of the yeshivah in Sura, in present-day Iraq; and died in the year 942 C.E. He was one of the first rabbis to write extensively in Arabic, and is considered the originator of Judeo-Arabic literature. He is best known for his magnum opus Emunot V’deiot (“The Book of Beliefs and Opinions,” or its longer, more complete name, “The Book of the Articles of Faith and Doctrines of Dogma”), which he completed in the year 933 C.E. Rabbi Saadiah Gaon wrote this work after seeing the confusion and ignorance among many of the Jews about their own faith. It is the first systematic presentation and philosophic foundation of Jewish thought and dogma.

He also wrote works on many other topics, including Hebrew grammar, Jewish law, and polemics against the Karaites. Additionally, he wrote a translation of Scripture into Arabic, with a very valuable commentary. This masterpiece is called Tafsir.

See more on Rabbi Saadiah Gaon here.

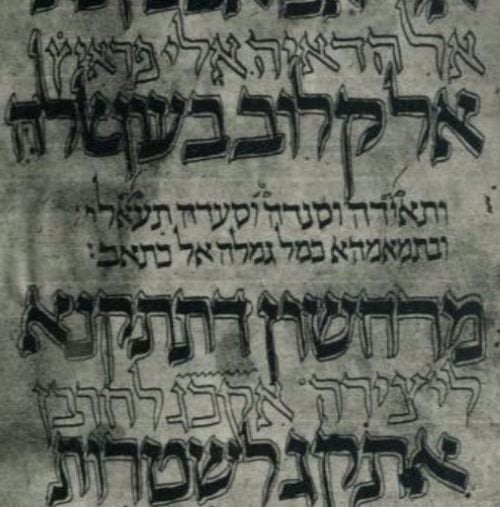

2. Al Hidayah ila Faraid al-Qulub (Chovot HaLevavot—“Duties of the Heart”), by Rabbeinu Bachya

Not much is known about Rabbi Bachya ben Yosef ibn Paquda, other than that he lived in 11th-century Spain and served on the rabbinical court there. He is famous for his work Chovot HaLevavot, “Duties of the Heart” (or as it was originally entitled before being translated into Hebrew, “Book of Direction to the Duties of the Heart”). Rabbi Bachya, or Rabbeinu Bachya, as he is more commonly known, writes that he wrote the book after observing that many Jews paid attention only to the outward observance of Jewish law, “the duties to be performed by the parts of the body,” without regard to the inner ideas and sentiments that should be embodied in this way of life, “the duties of the heart.” As such, Chovot HaLevavot deals with commandments based on the mind and emotions, such as thinking about the unity of G‑d, love of G‑d and trust in G‑d, but also hypocrisy and skepticism, humility and repentance.

Like the other works mentioned here, Chovot HaLevavot has become one of the foundational works of Jewish ethics and has been translated into many languages, including Hebrew, Latin, Judeo-Spanish, Italian and English.

3. Kitab al-Ḥujjah wal-Dalil fi Nuṣr al-Din al-Dhalil (The Kuzari—“A Defense of the Despised Faith”), by Rabbi Yehudah HaLevi

Rabbi Yehudah Halevi was a 12th-century Spanish Jewish physician, poet and philosopher. Throughout his life, Rabbi Yehudah dreamed of settling in the Land of Israel. He coined the famous phrase “My heart is in the East, but I am in the farthest West.” Toward the end of his life he set out for the Holy Land. Legend has it that upon reaching Jerusalem and beholding the Temple Mount, he rolled on the ground in ecstasy and composed “Tzion Halo Tishali.” At that moment, an Arab horseman saw him and trampled him to death. “Tzion Halo Tishali” is sung to this day as part of the Kinnot elegies traditionally recited by Jews throughout the word on Tisha B’Av to mourn the destruction of both the First and Second Temples in Jerusalem.

Rabbi Yehudah Halevi is best known for his masterful work The Kuzari, or as it is fully entitled, “The Book of Refutation and Proof on Behalf of the Most Despised Religion.” The Kuzari is structured as a dialogue between a rabbi and the king of Khazaria (a country located in present-day Russia and Ukraine), covering topics such as the fundamentals of Judaism, prophecy, the afterlife, the land of Israel, the Hebrew language, the benefits of communal prayer, the Sabbath, astrology, and determinism vs. free will. The Kuzari is a timeless classic and and is regarded as one of the most important polemical and apologetic works of Jewish thought.

See more on Rabbi Yehudah Halevi here.

4. Maqala Fi-Sinat Al-Mantiq (Millot HaHiggayon—“Treatise on Logical Terminology”), by Maimonides

Born in Cordoba, Spain, in the year 1135, Rabbi Moses ben Maimon, the RaMBaM—or Maimonides, as he is commonly referred to—was a philosopher, astronomer, and physician to the court of Sultan Saladin in Egypt, and is perhaps the most famous of the Jewish scholars listed here. Maimonides was a prolific writer, and at the age of 16 authored Millot HaHiggayon (“Treatise on Logical Terminology”), a study of various technical terms that were employed in logic and metaphysics. Although his magnum opus, the Mishneh Torah, in which he gathered and codified all of Talmudic law in an orderly and systematic fashion, was written in Hebrew, most of his other works were written in Judeo-Arabic.

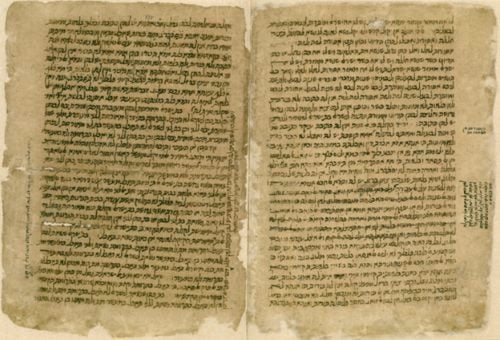

5. Kitab al-Siraj (Peirush HaMishnayot—“Commentary on the Mishnah”), by Maimonides

At the age of 23,while fleeing with his family from the Almohads (a fundamentalist Muslim dynasty that took over Cordoba),Maimonides started his commentary on the Mishnah, a massive work written in Arabic and subsequently translated into Hebrew by the famous ibn Tibbon family. In it he not only explains each mishnah, but also includes important background information such as a record of the transmission of the Oral Law to the leaders of each generation and an articulation of the 13 fundamental beliefs of Judaism.

6. Kitab al-Farai'd (Sefer HaMitzvot—“Book of Commandments”), by Maimonides

Also written in Arabic, this work is an enumeration of the 613 mitzvahsof the Torah. In the introduction, Maimonides enumerates 14 rules for determining which Divine commands are to be included in the 613.

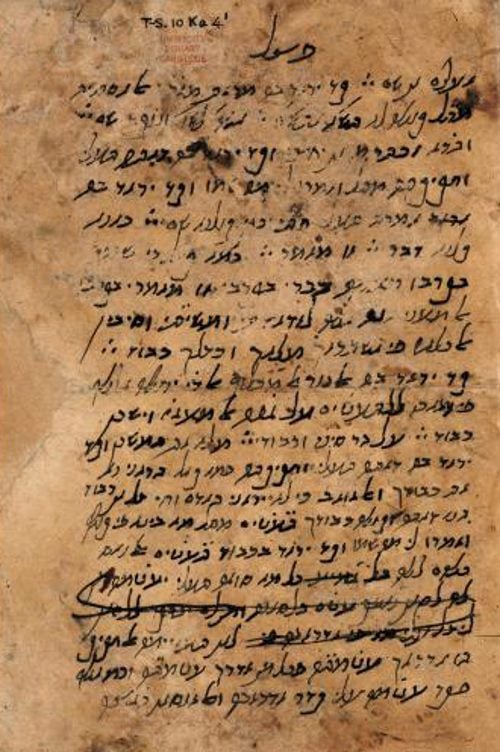

7. Dalalat al-Ha'rin (Moreh Nevuchim—“Guide for the Perplexed”), by Maimonides

A treatise on Jewish philosophy written in Arabic, Moreh Nevuchim discusses concepts such as the nature and existence of G‑d, the purpose of Creation, G‑d and His relation to the universe, the meaning of life and human destiny, the origin and underlying reality of evil, free will, Divine Providence and omniscience, Divine justice, revelation, the purpose and reasons for many of the mitzvahs of the Torah, and the true way of worshipping G‑d.

See more on the life and works of Maimonides here.

Join the Discussion